In the (proposed) 1899 Hague Regulations, the basic premise of the law of occupation was stated:

The country invaded submits to the law of the invader; that is a fact; that is might; but we should not legalize the exercise of this power in advance, and admit that might makes right (Beernaert in Benvenisti, 2012, 90).

In the fourth Geneva Convention (GCIV) (which was crafted to with the “aim of imposing on occupants ʻa heavy burden”) (Benvenisti, 2012, 97), the norm was codified that the occupant (occupier) must take three considerations into account: “itʻs own security interests, the interests of the ousted government, and those of the local population, which may be different from the interest of their legitimate government” (Benvenisti, 2012, 69).

First Geneva Convention, 1864

The norms of GCIV were formed in the context of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, which created an expectation that during occupation the occupying military and the civilian population could be kept at a distance from each other and even co-exist relatively harmoniously (Benvenisti, 2012, 70). As for changes to law, they were to be kept at an absolute minimum, but were allowable for the purpose of making occupation practicable and functional on the ground. Benvenisti (2012, 90) notes that the rule that changes to law are only when “absolutely necessary … has no meaning” because the occupant is never absolutely prevented from complying to local law.

Article 43 of the GCIV was a mandate to “restore and ensure public order and civil life” – this came to be seen as an “incomplete instruction to the occupant” because of the conflicts of interest between occupant and the ousted government (Benvenisti, 2012, 71).

Changes to the law of occupation also continued as human rights became more of a concern to the international community. As this occurred, actual occupants began to seek to avoid the responsibilities of occupation by “purport[ing] to annex or establish[ing] puppet states or governments, rely[ing] on ʻinvitations’ from indigenous governments [the Soviet/Russian formula]” and other means (Benvenisti, 2012, 72).

But as is often pointed out, these means are not legitimate as GCIV states “the benefits [or applicability] of the [Geneva] Convention shall not be affected … by any annexation … of the whole or part of the occupied territory.” In short, the occupant retained the duty to fulfill its obligations under the law of occupation (GCIV in Benvenisti, 2012, 73).

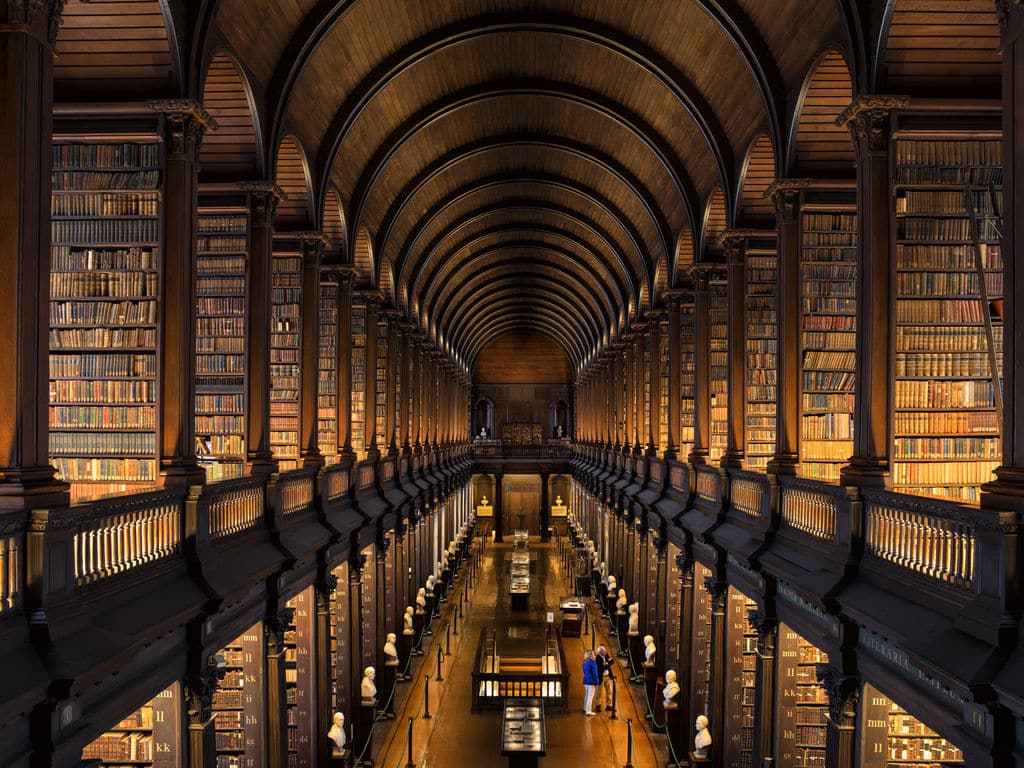

As with all legal documents and doctrines, however, it is “impossible to read the drafting history of the GCIV without paying close attention to the diverse concerns of the different state representatives” (Benvenisti, 2012, 98). That is to say, it is contingent on the conditions of the time and context in which it was crafted.

HUMAN RIGHTS

As it developed in the twentieth century, the human rights regime came to decenter the law of occupation’s emphasis on the agency of states as the only actors. People came to play a role in international law, under which previously only states were subjects. In the occupation of Iraq, for example, Amnesty International pushed for changes in Iraqi law – normally in contravention of the law of occupation – for the purpose of the protection of human rights. Occupation was in this case seen as an opportunity to improve conditions for the citizens of the occupied state (a rare, but quite possible scenario). Sharia law was in this case seen as “incompatible” with GCIV rights (Benvenisti, 2012, 103).

NECESSITY

Keanu Sai has used the “doctrine of necessity” as a justification for forming the Acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom; the necessity of an “organ” to speak on behalf of the occupied state, in other words, necessitated the creation of a “government” whose legitimacy would otherwise be highly questionable. Benvenisti notes this doctrine as a “recognized justification for legislation by the occupant,” but noted that it does not apply to the civil and criminal laws of the occupied state: “the penal laws of the occupied territory shall remain in force,” (Benvenisti, 2012, 96) ostensibly to prevent draconian trials and execution of resisters against the occupation. However, it is also recognized that the occupant would be “prevented from respecting the laws in force” in the rare case that they “conflicted with its obligations under international law, especially [the GCIV] (brackets original)” (Benvenisti, 2012, 102).

DEBELLATIO

Sai also notes that Debellatio, or conquest, while seen as a legitimate form for the transfer of sovereignty, was essentially outlawed in the Americas – by the United States and some of the recognized sovereigns in South America – because they feared their former colonial overlords would re-conquer them. This, in his view, was the purpose of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine. As Jay Sexton notes in his book The Monroe Doctrine, “American statesmen exploited fears of foreign intervention in order to mobilize political support” (Sexton, 2011, 12). Sexton also notes how the Tyler Doctrine (actually proclaimed in 1842 by secretary of state Daniel Webster) “effectively extended the 1823 message [the Monroe Doctrine] to Hawaiʻi” (Sexton, 2011, 112). As a result, the United States does not recognize debellatio – conquest – as a legitimate form of transferring sovereignty. This quells any argument that even though there was no conquest of the Hawaiian Kingdom, “there would be.”

MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES

The occupant is allowed to collect taxes, “as far as is possible, in accordance with the rules of assessment and incidence in force … to defray the expenses of the administration of the occupied territory” (Benvenisti, 2012, 81). In other words, the occupant should not, as was seen in the film The Last Emperor, make the occupied “pay for its own occupation” as the Japanese ambassador says to the Emperor of Manchuria (Manchukuo). The occupant is also bound by the general rules regarding property of usufruct – the use of land without destroying it (Benvenisti, 2012, 77). This is relevant to the U.S. presence in Hawaiʻi as evidenced by the more than one hundred Superfund sites at Pearl Harbor alone.

NATIONALS OF THE OCCUPYING POWER

My own understanding of the law of occupation is that it strictly prohibits the “overwhelming” of the nationals of the occupied state with settlers from the occupying state, as was done by Russia to Estonia and other Baltic states. Benvenisti treads very lightly here, noting only that settlement need only avoid “impinging on the rights” of the citizens of the occupied state. It is possible (though I donʻt mean to hastily accuse him) that his status as an Israeli influences this light treatment of settlers, and he does mention Israel, the West Bank and Gaza in the very short section on this topic (Benvenisti, 2012, 106-107).

Was the Hawaiian Kingdom obligated to the Monroe and Tyler Doctrine? If not then can we restore the government to our laws?

LikeLiked by 1 person

No – more like the victim of those doctrines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So what about the second question? Do we have recourse

LikeLiked by 1 person

International law can reasonably be seen as a construct of legal fiction. In other words, it’s a series of “gentleman’s agreements” whereby all State parties are obligated under binding law, but without enforcement of that law, State parties may ultimately act however they please — international law is a system based on an agreement to comply. Whether or not a State actually does is dependent upon who can make them comply.

In a sense, our recourse is dependent upon U.S. compliance with its obligations under international law. There are a number of instances (such as the war in Iraq) where the U.S. was in violation of its international law obligations, but it continued to do as it pleased. Another such instance is the U.S. use of waterboarding in violation of the UN Convention Against Torture (CAT). The U.S. has signed and ratified the CAT, making the state an obligated party bound by international law and yet, they still violated the treaty.

The short answer is that, yes, we do have recourse. However, the truth is that recourse may seem like an impossible request and would require significant international support and civil unity in order to be achieved — massive people movements.

International law lacks the kind of enforcement often employed by domestic courts — police power. Shaming is often used by NGOs through international awareness to pressure governments to comply with their obligations under international law. With enough of the world pointing their fingers at the U.S. with regard to Hawai’i, we may indeed achieve recourse.

It’ll take a significant movement of people in addition to world-wide education.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for helping to sort out what is in many ways a bit of a muddle.

LikeLike

Mahalo Z.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Sacred Mauna Kea.

LikeLike

We have won the legal argument, but as the saying goes give me a place to stand and I can move the earth. Find that legal footing and know change

LikeLike