This post is part of the continuing “On” series: others include On Capitalism, On Freedom, On Constitutionalism and On Privilege.

In Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, Gordon Gecko – famous for the line that defined the 80s, “greed is good” – relates the secret of his success: “I own stuff.”

By acquiring ownership of appreciating assets, investors buy low and sell high, and real estate is a prime example of this. But as Iʻve come to own property, it has begun to dawn on me that one never really owns anything. There are many ways that a property can be foreclosed on, beyond simply failing to pay the “mortgage” (you actually pay the loan, the mortgage is the contract allowing foreclosure): failure to pay taxes (a tax lien), failure to pay maintenance fees, failure to pay any “mechanic” who does work on your house (a mechanic’s lien). Taxes in some high-value areas can be in the thousands per month, so even if you own your property free and clear, the cost of living there can be prohibitive, as much as a “mortgage.” Further, you donʻt really own property at the most fundamental level. The legal concept of “dominium” means that the sovereign owns all property at a level “beneath” your “ownership” – what you have is actually a bundle of protected rights to the property: the right to use and enjoy, exclude others, etc. (though this last right is abridged in Hawaiʻi due to Native Tenant Rights).

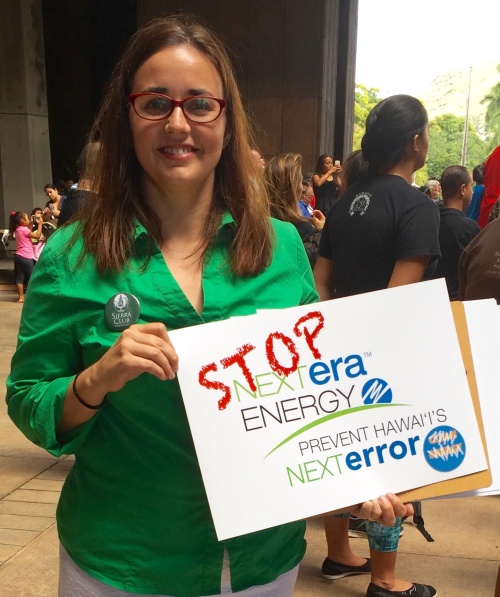

At a conference on occupation at Cornell last May (my attendance was due to this article I wrote for The Nation), we looked at the term from various perspectives, including the simple occupation of land

As I write this, Hawaiʻi is in crisis. The basic necessity of a roof over oneʻs head is one of the most difficult “commodities” to afford, and hereʻs the thing: many of us are responsible for this state of affairs. Homeowners benefit from raises in housing prices, and have a vested interest in the continuation of this state of constant increase – that is, as individuals. Even this benefit is, in a sense, short term. When you sell your high priced property, you have to buy back in to an inflated market. Also, housing becomes much more expensive for your children, who youʻre trying to help get along in the world. It becomes a form of generational warfare. The situation is so extreme, that even renting is becoming a difficult proposition for many – credit checks, first and last monthʻs rent and/or deposits can make renting something only for the very well-off. (If you had great credit wouldn’t you be buying instead of renting?). According to an article in Civil Beat, thirty percent of renters are spending half of their income or more on rent, making them very vulnerable to shocks, like divorce, death in the family or medical problems. Add this to the fact that most Americans donʻt have $1000 for emergency expenses, and the situation is dire indeed.

Ironically, some long-term studies show that property, when adjusted for inflation, has not had real increases in a century. Any exceptions to this are bubbles. So are we in the midst of a very protracted bubble? If so, we may want to change our long-term approach to wealth management. I wrote earlier that the wealthy are beginning to thinking about access rather than ownership, an this has begun to trickle toward the middle class and working poor. We need to begin to question the very fundamental assumption that the market is the best mechanism for allocating scarce resources, like real estate. There are some small moves in this direction: Kamehameha Schools (normally a very aggressive developer) is developing its Oʻahu North Shore lands in a way that takes some other factors into account. Priority for a new development in Haleʻiwa will be given to local (that is, North Shore, and often Hawaiian) families who fall into the “gap group” – imagine a teacher married to a fireman. They arenʻt in lucrative positions, but are a stable bet to pay their loan and stay in their house for decades, rather than sell at the first uptick in prices.

Perhaps we should try to return to traditional Hawaiian ways of thinking about ownership. According to a source I cite in my dissertation, Hawaiians had very few possessions. A man, for instance would own only a handful of items related to his trade. So the idea that one could own land was certainly foreign – even chiefs didnʻt own land – they controlled it for a period of time, until the next kālaiʻāina (land division).