This post, along with the one on Rousseau, Plato and many to follow, are part of an upcoming project – stay tuned.

The United States incorporated a Lockean notion of relation of individual to state, a notion that was “dominant at the time when the [US] Constitution was adopted.” In common parlance, the term property is used as a noun. One is said to own “property,” i.e., a piece of property, an object. Locke’s time used property as a right, as in “I have a property in that land.” This shift occurred sometime in the seventeenth century [see Appleby] in Europe, and was present at the founding of the US, but in Hawaiʻi, it was more visible, occurring in the time period in question, the 1840s and 1850s. So in addressing the question of the transition from property as a right to property as an object, some of the associated trauma can be attributed to the fact that the shift was both later and more rapid in Hawaiʻi than in Europe.

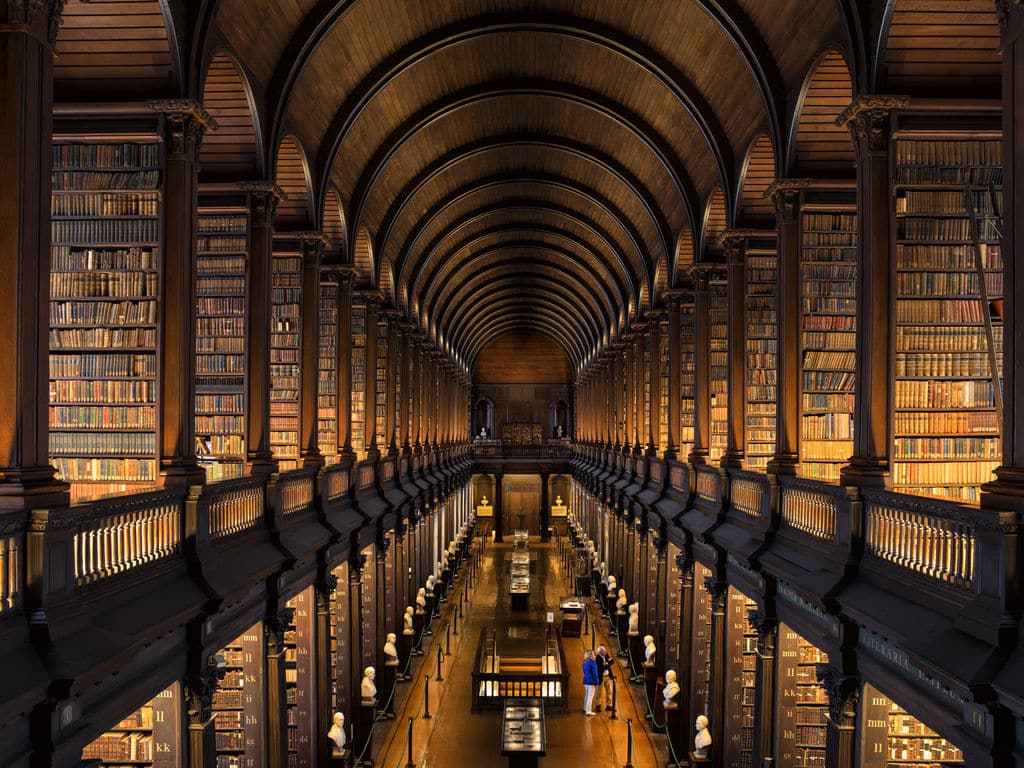

John Locke

Locke expounded his notion of property in his Two Treatises of Government, Second Treatise (1690):

… every Man has a Property in his own Person. This no Body had any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the State that Nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his Labour with, and joyned to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his Property. It being by him removed from the common state Nature placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it, that excludes the common right of other Men. For this Labour being the unquestionable Property of the Labourer, no Man but he can have a right to what that is once joyned to, at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others.

Sec. 43. . . . . ‘Tis Labour then which puts the greatest part of Value upon Land, without which it would scarcely be worth any thing . . . . For ’tis not barely the Plough-man’s Pains, the Reaper’s and Thresher’s Toil, and the Bakers [sic.] Sweat, is to be counted into the Bread we eat …

Sec. 45. Thus Labour, in the Beginning, gave a Right of Property, where-ever any one was pleased to imploy it, upon what was common, which remained, a long while, the far greater part, and is yet more than Mankind makes use of.

The application of Lockean ideals in Hawaiʻi was premised on a particular psychology subcribed to by missionaries:

In some ways the missionaries … were equipped with a full-fledged theory of the human mind and society … Their psychology started with the empiricist idea od the mind as filled with custom, hence subject to outside influence and change. The follies and whims of the human mind, perpetuated by custom, as Locke and the enlightenment thinkers would say, are a result of insufficient use of the reason due to social circumstances (Mykkänen, 2003, 80).

Responding to Hobbes’ more radical notion that “everyman” has a right to everything, Locke held that it was a “ridiculous trifling to call that power a Right, which should we attempt to exercise, all other Men have an equal Right to obstruct or prevent us” (Tully, 1980, 74). This separation of rights represented a building of consensus over rights in property that the state was being encouraged to protect.

The foundation of the debate rested on the notion of natural rights, on the existence of which there was considerable agreement. The debate centered, instead, on the manifestation of natural rights in the actual world of property ownership. The interpretation of these rights rested, in turn, on the idea of the social contract. Pufendorf held, in response to Hobbes, that “rights of property have no higher sanction than the laws which men consent to in entering political society” (Tully, 1980, 75).

Ivison, Patton and Sanders summarize the larger picture of interaction between “Western” political thought and Indigenous societies, values and systems of property:

Western political thought has often embodied a series of culturally specific assumptions and judgments about the relative worth of other cultures, ways of life, value systems, social and political institutions, and ways of organizing property. As a result, egalitarian political theory has often ended up justifying inegalitarian institutions and practices” (Ivison, Patton and Sanders, 2).

They contend that “finding appropriate political expression for a just relationship with colonised indigenous peoples is one of the most important issues confronting political theory today” (Ivison, Patton and Sanders, 2).

Defining “rights” as that “securing or protecting fundamental human interests, for example, those to do with property or bodily integrity,” they note that recognition of Indigenous rights will entail a fundamental alteration of those rights. Further, the note the failure of western political theory to enter into dialog with Indigenous peoples over the issue of rights in general, and, I would add, property rights in particular.

Ivison, Patton and Sanders also address the issue of indigenous title, and hold that it is “more about the continual definition and redefinition of relationships rather than the simple vindication of a property right.” This notion suggests the primacy of communal title and further its contrast with individual title. In fact, New Zealand’s Maori Land Court had as its primary task the “individualisation” of Maori title – a practice viewed as facilitating alienation of Maori lands.

Tully (99) notes that, for Locke, “it is never the case that … property is independent of a social function.” He distinguishes between property as a natural right and “political property,” which succeeds it and is only then private property. Locke opposes Filmer, Grotius and Pufendorf on this point. He holds that the natural property rights in the state of nature precede “the systems of property that arise later with the introduction of money and the creation of government.”

This, of course, is subject to critique, as the notion of a state of nature prior to government was what facilitated the doctrine of terra nullius. Thus the notion of a state of nature itself is contingent on one’s ability to see a government – which settlers in Australia claimed not to be able to do. Locke had a similar blind spot when it came to the “new world.” Locke worked as an aide to the Lord Proprietor for the Carolina colonies. His work justified slavery in the Carolinas and he was a shareholder in the Royal African Company, which was involved in the African slave trade. Locke clearly believed in property, but his belief in liberty was more constrained. Farr (2008), however, holds that Locke forwarded a just-war model justifying slavery, but one that did not apply in the Americas, but only in Stuart England.

Between Locke’s Eurocentric notions of property and government and inconsistent position on slavery, the implementation of a Lockean private property regime in Hawai’i was indeed problematic.